Previous Exhibitions

2024 “Invasion of Australia via Botany Bay….#2”

2023 “To Botany Bay…. ? #1”

2021 Group Exhibition Castlemaine Fringe Festival.

2018 Arts Open. “From Invasion to Recognition.”

2017 Castlemaine State Festival. “Dja Dja Wurrung Country.”

2016 Arts Open. “Revisiting Indigenous Cultural Landscapes.”

2015 Castlemaine State festival. “Djaara Country. We’re Standing in It”

2014 Arts Open. “Invasion of Australia Felix”

2013 Art Fields. “Land Rush to Gold Rush”

2013 Castlemaine State Festival. Garden Of Eden or Indigenous Cultural Landscape?

2012 Arts Open. Major Mitchell – “Journey to the Australian Felix.”

2011 Major Mitchell Symposium & Exhibition

2011 Castlemaine State Festival. Expedition Exhibition

2010 Followed the Major Mitchell Expedition of 1836

2009 Castlemaine State Festival. Journey to Gondwana Felix

2007 Castlemaine State Festival. Rare and Endangered. Special and Unique

2005 Castlemaine Fringe Festival. Beyond the Tigerlily

2003 Mamunya Festival, Saffs Café. Castlemaine

2001 Castlemaine Fringe Festival. Group Show

1999 Group Show, Azibi. St Kilda

1998 Solo Exhibition. Brunswick St Fitzroy

1996 Greenpeace, Environment Day Exhibition

1996 Galvanize, Group Show, Chapel off Chapel Gallery

1995 Aquarium Cafe, Brunswick St, Solo Show “Day on Earth”

1995 Riso Print Gocco, High Commendation

1994 Riso Print Gocco Print Award, Gold Prize

1993 Mad Hatter’s Tea Party Design and Production

1992 Mario’s Cafe, Brunswick St, Solo Show

1992 Young Australians Achievement Award

1991 La Trobe University, Womens’ Group Show

1990 Friends of the Earth, Group Show

1989 Artists for the Forests, Bondi Pavillion

1988 Fabric design Award, Sebel Town House. Sydney

1987 East Sydney Technical College. Group Show

1986 Suitcase, Group Show, Gallery 404. Sydney

1985 Young Artists Exhibition, Lower Town Hall. Sydney

1985 Barry Stern Print Award

Eliza Tree

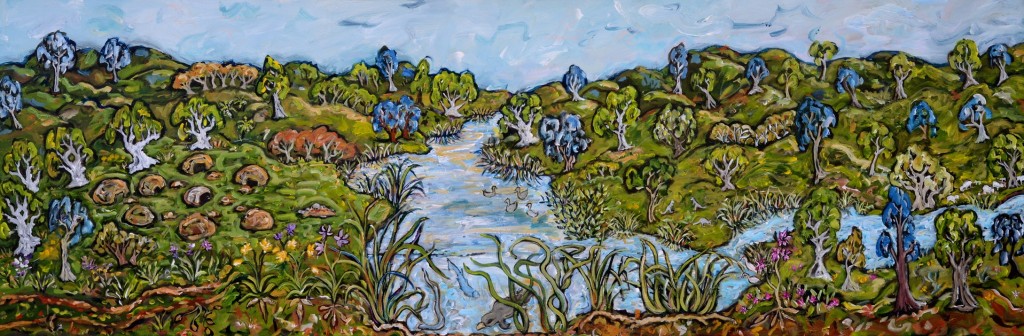

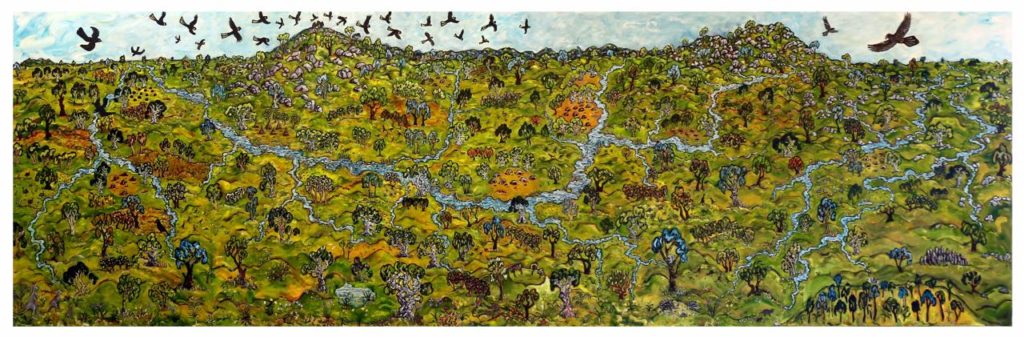

From Invasion to Recognition.

Revisiting Indigenous Cultural Landscapes, before the gold rush.

1835 – 1851.

Paintings, Audio Visual, Maps & Text.

Sat 10th – Sun 18th March 2018

10 am – 5 pm

Loft Gallery. Exhibit 22.

22 Hargraves St Castlemaine.

In 1835 John Batman established an illegal settlement in Port Phillip Bay.

In 1836, Major T L Mitchell’s Expedition journeyed through Dja Dja Wurrung Country, the Castlemaine region – describing it as the “Australia Felix”

-the happy & abundant Australia.

Home of the Dja Dja Wurrung Peoples, for many millennia,

Living rich Cultural and Spiritual lives,

in abundant cultural, cultivated and created Landscapes.

Within a diverse & extraordinary bio region.

It’s time to revisit this forgotten Chapter.

Exploration, Invasion, Land rush to Gold rush. 1835 – 1851.

It’s time to broaden the grand narrative of the colonial gold rushes,

to reveal Indigenous Cultural landscapes, enjoying a temperate climate within a well watered and abundant geological

& ecological bio region;

:Land Grab and Pastoral Invasion of an unprecedented scale; Dispossession & dislocation of Indigenous Peoples;

Before the wild and woolly Victorian Gold Rush(s).

Paintings, Audio Visual, Maps & Text.

Sat 10th – Sun 18th March 2018

10 am – 5 pm

Loft Gallery. Exhibit 22

22 Hargraves St Castlemaine.

![]()

![]()

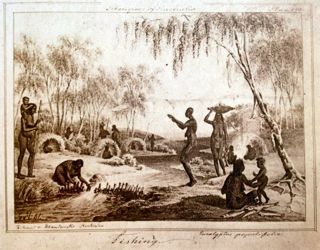

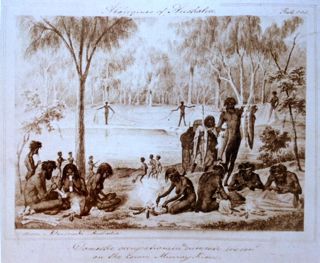

“Pastoralism…required huge stretches of land, the same land that was at the heart of Aboriginal society. The squatters’ sheep and cattle ate up the pastures on which the native game fed, and demolished the yams and mirr-n’yong roots which traditionally served as a staple in the Aboriginal diet…

Around Melbourne and in rapidly settled areas, eeling spots, rivers, traditional camping places and sacred sites were fenced off and the Aborigines forbidden entry. In the interior, waterholes that had previously provided fish, duck and eels were spoiled by sheep or closely guarded by hutkeepers.

Aboriginal campsites chosen for their availability of water and seasonal food supplies, were taken over by squatters, who were attracted to them by the same advantages…Wherever the white man went, the native game was eaten out by sheep or shot for sport. Deprived of their former food sources, the Aborigines either starved…or obtained food in some other way from the whites.” [i]

[i]M.F. Christie, 1979

Eliza Tree

Dja Dja Wurrung Country

Revisiting Indigenous Cultural and Cultivated Landscapes

March 18 – 25, 2017

12 – 5 pm

Launch: Sun 19th.

Morrell Gallery

139 Mostyn St Castlemaine.

www.majormitchellexpedition.com

Re-evaluation of indigenous culture and lifestyle through images, maps and wider reading, reveals a different picture than previously painted. Aboriginal land management, cultivation and hunting techniques rewrite the story: not subsistence nomads but many highly evolved and organized family groups, living in an abundant environment, practising complex social, cultural and religious traditions. Indigenous life was very Regional with deep connection with Country. Resources were actively managed, with firestick farming, cultivation respectfully managed the clans’ territorial country and ensured abundant resources.

The availability of a range of maps and texts, provides an opportunity to discover and examine the resistance of the Djaara people, the rapid and violent dispossession of the land from the Dja Dja Wurrung, in one of the fastest expansions of Empire on the newly settled continent.

Major Thomas Mitchell first explored and mapped this region in 1836 on his homeward journey through the Australia Felix, in anticipation of informing the Colonial Government of new pastoral lands. Despite evidence of the longevity of indigenous habitation and their continuing presence, Mitchell’s reports favoured the Colonial narrative of settlement and spurred a land rush from the north. “Certainly,” he wrote, “a land more favourable for colonisation could not be found. Flocks might be turned out upon its hills, or the plough set at once to the plains.” He described the area in glowing terms. “No primeval forest require first to be rooted out, although there was enough of wood for all purposes of utility, and as much as even a painter could wish.”

By 1837 and into 1838, overlanders began to travel southwards with their herds and flocks. This caused changes in the Colonial policy with the annexing of Crown lands and the selection of pastoral lands, enormous tracts for squatters to graze. The settlement of Port Phillip and Mitchell’s 1836 expedition were followed by a pastoral invasion ‘of unprecedented scale’. William Barker selected a run of 30,000 acres, with 7,000 sheep and Donald Cameron established himself across 20,000 acres with 5,000. Together, these two pastoral runs subsumed the traditional lands of the Galgal Gundidj clan of the Dja Dja Wurrung, including the Forest Creek watershed.

Arts Open 2016

Eliza Tree is presenting her exhibition of paintings, maps and text, to share her insights into the early history of our region. The collection reveals a fascinating cultural, ecological and social landscape beginning with Dja Dja Wurrung occupation and ownership of the country. She uses historical documents and sources to question our assumptions of exploration, pastoralism, colonial expansion, and the time leading up to the gold rush.

In 2010 Eliza traced the 1836 Expedition of Major Mitchell, and has since continued to research and explore the descriptions of Major T L Mitchell and others, to understand and transcribe the landscape he saw and described in such glowing terms – the Australia Felix.

“Following Major Mitchell’s journey to the Australia Felix – the abundant or happy Australia – in 2010, opened my eyes in a fresh way. Following his maps and descriptions of the land has given me the opportunity to translate it into a visual narrative through my paintings,” says Eliza.

Her research, focused on Central Victorian Jaara Country, has also revealed many other early texts, unearthing an intriguing picture of times prior to the gold rush.

“There’s fascinating information available. It’s a matter of weaving alternative narratives. It’s useful both in understanding the past, and recreating the future. LandCare groups throughout the region have done amazing works to restore creek lines and waterways, especially the Forest Creek area in and near Castlemaine city which was so dramatically disturbed during the gold rush, and other areas infested by weeds and willows.”

Eliza Tree’s exhibition focuses on Forest Creek as the heartland of Djaara Country. Beginning with exploration and pastoral invasion she uncovers a new history of pre-gold rush and beyond. She hopes to expand our perception of Indigenous stories of both culture and nature and help to restore an understanding and a vision for today, into the future.

Lyttleton St Studio. 94a Lyttleton St, Castlemaine.(Corner of Urquhart)

Launch: Thurs 13th August 6 – 8 pm

Open: Fri 14th – Sun 16th , 1 – 5 pm.

Sat 22nd – sun 23rd, 1-5 pm.

Sat 29th – Sun 30th, 1 – 5 pm

Join us for a warming gluvine and chat beside the fire,

or by appointment – M: 0409 209 707.

Eliza Tree

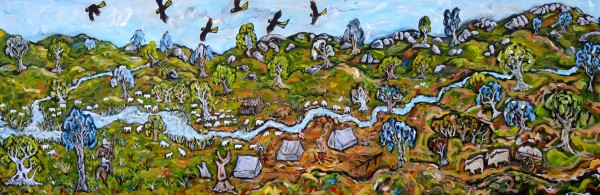

Invasion of the Australia Felix

“Recollections of Squatting in Victoria”

Paintings, Maps & Text

8-10 March, 2014

10am – 5pm

94a Lyttleton St, Castlemaine

Artist talks daily at 11am & 2pm

About the Project:

Old perceptions. New understandings.

Questioning the meta-narrative of “settlement / invasion” of Victoria.

By revisiting early maps, documents and publications I have sought to question the dominant ideologies of colonial times and beyond, which form the base of our understanding of “peaceful settlement” of Australia. My research reveals an extraordinary Indigenous cultural landscape and concealed stories of dispossession.

The early days on the frontier are omitted and overlooked in favour of a more palatable and heroic view of our colonial past. The settlement of South Eastern Australia in the 1830s and 40s was neither peaceful nor accidental. “Terra Nullius” was a cruel lie that enabled invasion and theft on an extraordinary scale. It was clearly apparent that the Indigenous peoples did own and cultivate their country. This is revealed in early publications, which I re-visited in contemporary times with interdisciplinary and revisionist interpretation.

“It may perhaps be doubted whether any section of the human race has exercised a greater influence on the physical condition of any large portion of the globe than the wandering savages of Australia.” E. M. Curr, 1883.

Even the rare individuals who appreciated and understood Indigenous peoples during exploration and settlement chose to ignore their humanity and justified the invasion on deeply prejudiced values of ‘civilisation’. Major Mitchell, who understood some indigenous language and the complexities of Indigenous culture, chose to proclaim in 1836 that “the natives roam over the earth incapable of civilisation and the only arts they know are those with which to destroy each other.” This statement influenced a wider denial of Indigenous humanity and land ownership – paving the way for invasion on an unprecedented scale” (James Boyce)

Indigenous culture is sophisticated and complex, having evolved over many thousands of years and generations. Adapting and connecting deeply with language, spirituality, customs, lifestyles and technologies interconnected and influenced by the local geography, ecology and climate. We underestimate these complexities as so rarely were the positive aspects of Indigenous life and culture described in the early annals.

South Eastern Australia was heavily populated by Indigenous nations, particularly the Murray Darling Basin. Despite the existence of maps and early records, the majority of Australians remain ignorant of the local clans and tribes which owned and nurtured the land. How rarely we hear the names spoken or the stories of early dispossession, despite being surrounded by Aboriginal words and names. Eg: Canberra, Wagga Wagga, Cootamundra, Wonthaggi, Yandoit, Yapeen, etc.

There is great need that we understand the terrible impact of farming and grazing upon our land and landscapes. The droughts, the floods and ultimately climate change which we clearly continue to perpetrate on the ecology of this fragile continent. One only needs to look at the Murray Darling Basin to witness the continuing impacts of environmental arrogance and ignorance.

The abundance of local environments was underestimated on two levels. The firestick farming practices were conveniently overlooked as was the clear influence of Indigenous practices on the landscape. Secondly, the impact of hard-hoofed animals on the waterways and country is very poorly understood.

Seasonal movement ensured maximum abundance and enhancement of the landscape, with Indigenous people being actively involved in burning, cultivating and harvesting a wide variety of natural resources. Food sources included underground plant foods, fresh meat, aquatic resources, reptiles and birds. These were systematically harvested and shared amongst the family groups who lived and travelled together. At times of great abundance groups would gather for extended periods. Many groups had semi-permanent habitations that were returned to regularly, especially on water ways and sources.

Every man, woman and child in South Eastern Australia had a possum skin coat. Unfortunately these were often stolen or traded, being replaced by European woollen blankets of inferior quality and warmth.

Hunting and gathering techniques were many and varied with great understanding of and respect for local resources. Enormous nets were used to catch emus and kangaroos, and as well to capture large quantities of water birds. Fire was used to replenish and expand grasslands that were also rich with tuberous and other plant foods. Trees contained hollows abundant in possums, birds and reptiles. Many of these animals are now extinct or endangered from white settlers’ excessive land clearance and introduced feral animals.

Another misconception is of the waterways, which were previously often a meandering chain of ponds or wetlands rich in herbage and aquatic resources. Eighty percent of found Indigenous artifacts are located close to creeks, rivers and springs. The extent to which these have been affected by hard hoofed animals and agriculture is extreme.

“Pastoralism…required huge stretches of land, the same land that was at the heart of Aboriginal society. The squatters’ sheep and cattle ate up the pastures on which the native game fed, and demolished the yams and mirr-n’yong roots which traditionally served as a staple in the Aboriginal diet…Around Melbourne and in rapidly settled areas, eeling spots, rivers, traditional camping places and sacred sites were fenced off and the Aborigines forbidden entry.

In the interior, waterholes that had previously provided fish, duck and eels were spoiled by sheep or closely guarded by hutkeepers. Aboriginal campsites chosen for their availability of water and seasonal food supplies, were taken over by squatters, who were attracted to them by the same advantages…Wherever the white man went, the native game was eaten out by sheep or shot for sport. Deprived of their former food sources, the Aborigines either starved…or obtained food in some other way from the whites.” Christie, 1979

Revisiting the early times is both fascinating and disturbing. We must acknowledge the Indigenous frontier war against dispossession and theft of lands and culture. It was not Gold that made Victoria, but Land and Water.