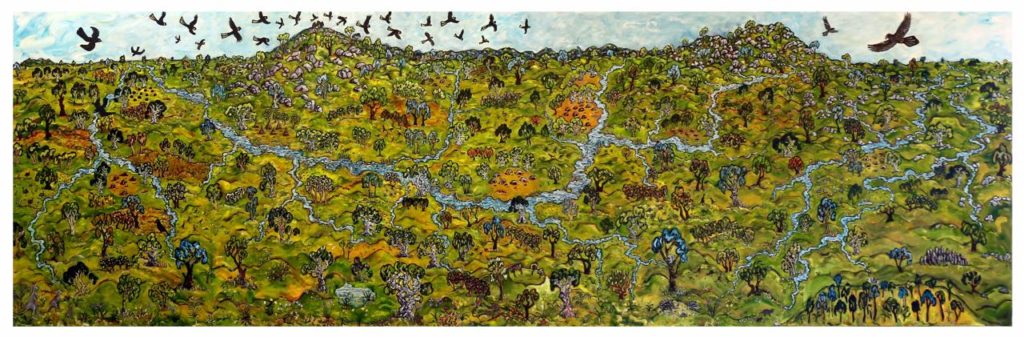

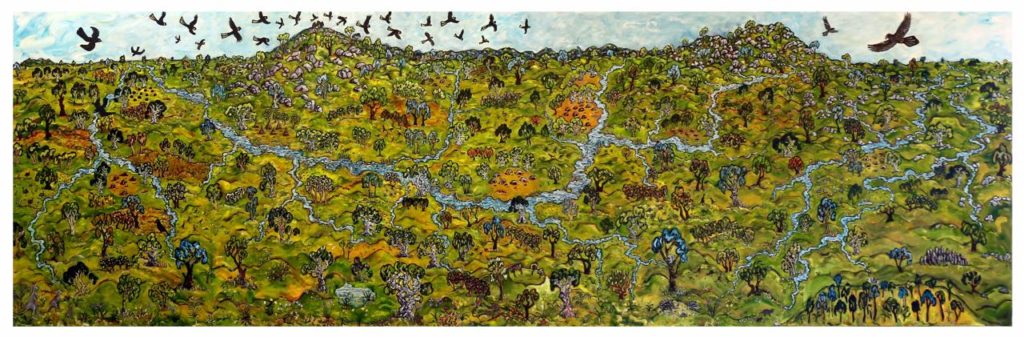

The original inhabitants, the Dja Dja Wurrung, lived in this area of central Victoria for 20,000 years or more, before exploration brought word of the ‘Australia Felix’ – the happy / abundant Australia. Re-evaluation of indigenous culture and lifestyle through images, maps and wider reading, reveals a different picture than previously painted. Aboriginal land management, cultivation and hunting techniques rewrite the story: not subsistence nomads but many highly evolved and organized family groups, living in an abundant environment, practising complex social, cultural and religious traditions. The indigenous ‘nomadic’ life carefully and respectfully managed the clans’ territorial country and ensured abundant resources.

The availability of a range of maps and texts, provides an opportunity to discover and examine the resistance of the Jaara people, the rapid and violent dispossession of the land from the Jaara, in one of the fastest expansions of Empire on the newly settled continent. Major Thomas Mitchell first explored and mapped this region in 1836 on his homeward journey through the Australia Felix, in anticipation of informing the Colonial Government of new pastoral lands. Despite evidence of the longevity of indigenous habitation and their continuing presence, Mitchell’s reports favoured the Colonial narrative of settlement and spurred a land rush from the north. “Certainly,” he wrote, “a land more favourable for colonisation could not be found. Flocks might be turned out upon its hills, or the plough set at once to the plains.” He described the area in glowing terms. “No primeval forest require first to be rooted out, although there was enough of wood for all purposes of utility, and as much as even a painter could wish.”

By 1837 and into 1838, overlanders began to travel southwards with their herds and flocks. This caused changes in the Colonial policy with the annexing of Crown lands and the selection of pastoral lands, enormous tracts for squatters to graze. The settlement of Port Phillip and Mitchell’s 1836 expedition were followed by a pastoral invasion ‘of unprecedented scale’. William Barker selected a run of 30,000 acres, with 7,000 sheep and Donald Cameron established himself across 20,000 acres with 5,000. Together, these two pastoral runs subsumed the traditional lands of the Galgal Gundidj clan of the Dja Dja Wurrung, including the Forest Creek watershed.

The narrative of pastoral invasion is significant, complex and overlooked, despite spanning the fifteen years immediately prior to the 1851 gold rush. Vast flocks of sheep and cattle were introduced into cultivated Indigenous landscapes, and they thrived. The waterways, previously described as a meandering chain of ponds, changed over fifteen years of use by squatters, to rushing and eroded creeks. The squatters selected and took up areas of land, always with the best access to water. The luscious verdure of grasses and herbage was rapidly diminished. This unpredictable, rapid and violent invasion was overshadowed by heroic stories of colonial hardship and by the ‘smoke and mirrors’ of gold rush settlement beginning in 1851.

The history of this region is written in its landscape and the land sets a stage for stories, myths and spiritual connections to be made. Forest Creek was the heartland and home range of the Galgal Gundidj clan of the Jaara tribes, who inhabited this region for millennia. Traditional stories include the local legend of giants throwing rocks at each other and creating Leanganook (Mt. Alexander) and nearby peaks. Volcanic eruptions can be traced geologically, to as recent as 10,000 years ago. The indigenous peoples created and transformed the landscape. They were the original ‘affluent society’ and the Dja Dja Wurrung were members of the oldest living culture on Earth. Their spirit inhabits the landscape.